DECEMBER 2011 I Came To Be Surprised

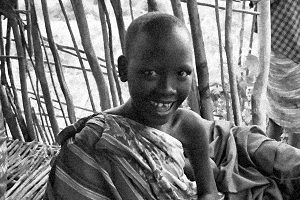

It was early evening. I had been flying all day. The high mountains of southeastern Congo reflected in the warm clear waters of Lake Tanganyika. The spectacular beauty hid the fighting still going on there over gold, diamonds, coltan and other minerals. I banked the plane into a tight turn, keeping the tiny, rarely used airstrip in view over my shoulder. It looked landable. It was. But the car I expected to meet me was nowhere in sight. As the plane came to a stop, two dozen young children in dusty and very basic clothes came running over to see. I opened the door. They were cautious but curious. I spoke with them and joked with them, asking if they were the night watchmen. They laughed and said no. I asked the oldest one, who wouldn´t have been more than 10, why he had come to the airstrip. “I came to be surprised,” he said, with a huge smile and wide opened eyes. I asked him, “Are you surprised?” He answered, “I am in awe.”

It was early evening. I had been flying all day. The high mountains of southeastern Congo reflected in the warm clear waters of Lake Tanganyika. The spectacular beauty hid the fighting still going on there over gold, diamonds, coltan and other minerals. I banked the plane into a tight turn, keeping the tiny, rarely used airstrip in view over my shoulder. It looked landable. It was. But the car I expected to meet me was nowhere in sight. As the plane came to a stop, two dozen young children in dusty and very basic clothes came running over to see. I opened the door. They were cautious but curious. I spoke with them and joked with them, asking if they were the night watchmen. They laughed and said no. I asked the oldest one, who wouldn´t have been more than 10, why he had come to the airstrip. “I came to be surprised,” he said, with a huge smile and wide opened eyes. I asked him, “Are you surprised?” He answered, “I am in awe.”

They asked when I was leaving. I told them it would be very early in the morning, with some doctors who had been working in their area. They asked if they could come to watch. I told them to be there before sunrise. They were. As the wheels lifted off the bumpy earth, the kids waved. I rocked the plane´s wings and banked into the dawn-thin line of light on the eastern horizon.

I don´t know if I´ll ever see them again. Still, as this year comes to an end with a promise of a new one to come, I know I will remember the child´s lesson.

What a great way to live. What a neat thing to do: to come to be surprised.Thank you all for your friendship over the years. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with surprises, and awe, and lots of laughter.

A Tanzanian Thanksgiving

NOVEMBER 2009

Dear Friends,

Every morning, as certain as sunrise, a group of very thin women meet me as I go out the door. They greet me in Swahili saying “Njaa, Bwana” “I´m hungry sir.” And I try to listen to their stories…

Another cool, clear, cloudless night in north central Tanzania. I was born in Michigan. One week without rain and the farmers talk about a drought. What would they think? Here, it is the sixth straight dry month. It hasn´t rained a drop. The cattle are gone — moved or dead. Cows are the people´s lifeblood. They are the babies´ postbreast milk. There is no other food. The unripe crops have long since withered on the stems. Her name is Naramat. It means “the one who delights in caring.” She is my same age, 61. Her husband hung himself from a tree one morning two weeks ago. Her son was a night watchman. He was killed in a robbery attempt one night in Nairobi at the factory which he was guarding. They sent his body home. But no money. Lots of young men need work. Plenty of potential night watchmen around. Her daughter has mental problems. She´s in and out of the hospital. Off and on medication. Doesn´t work very well — neither she nor the medicine. Oh…. and Naramat is blind. She is led here by her granddaughter. There are five grandchildren at home. But she is their mother. Her own daughter died of A.I.D.S. two years ago.

It´s quiet tonight. No wind at all. Merciful. With the winds come the dust. Choking. Blinding. Every step on the ground raises a puff. There are places now where we sink down into the fine powder half-way to our knees. We try to avoid those places when we walk. It gets harder to avoid them as the weeks go on. In a car, at noon time, the dust storm can be so dense that we creep along the main roads, headlights on, still only narrowly missing a stopped car or bus or truck. In the dust we see women and children kneeling down and digging out the roots where there once was grass. That is the only food left for the last surviving sheep or goat.

Naramat is at my front door. She calls softly to me. One of her granddaughters is with her. Both women, the young and the old, have sunken spots on the sides of their heads at their temples. (Try something. Touch your head there, one hand on each side. Open your mouth. Now close it. Feel the small muscle moving?) Naramat and her granddaughter have no fat left. Even that tiny muscle is wasting. “Can you help me?” she says. “It´s embarrassing to ask.” … “I´m hungry.”

WHAT IS LIFE WORTH? How much do we pay to save it? Maybe easy to play the guessing game half-a-world away. But she is at my door, standing in front of me. There are 79 others like her on the list that we have drawn up. Nearly all widows. They are caring for 265 children. Some people from one of the local parishes told me they want to build a church. They are asking the people to raise $65,000. I don´t agree. An average salary here during prosperous times is less than $35 a month. I remind them of the bible verse which says:

“True unspoiled religion in the eyes of God is this: coming to the help of orphans and widows when they need it.”

The rains will come, but meanwhile we wait. The dust will sprout green grass once again. And while we wait, we gather together and distribute what limited resources the mission has available. We try to see that those in the most dire straights make it through what are truly desperate times.

Fresh Peaches

DECEMBER 2008

DECEMBER 2008

Dear Friends,

Cancer took my left kidney in 2006. I survived an aircraft accident in 2007. I was alone on board and though I don´t remember how, I got out before the aircraft exploded and burned to dust. With 2008 nearly ending, I´m healthy, grateful to be alive and so…

I still have an African story to tell…

Ndepayan´s husband was killed while working as a night watchman in Nairobi several years ago. His death left her destitute and alone in raising three kids, two of whom have major health problems. She hardly had money to feed herself, let alone her three young children, and she had absolutely no money for heath care. In her desperation she did the only thing she could think of: hide the sick ones away.

I don´t remember how she found us. One day they were just here. She and her children, all in tattered clothes, just showed up at our door. The 11 year old Naramat, her oldest child, helped her carry Losieku, the youngest of the three. This small boy was born with spinabifida, a horrible birth defect that leaves the spinal cord uncovered. Tagging along behind, her second child, Loewuo (Low-AY-wu-o), was drooling from the side of his mouth. Apparently born healthy, early-on he started having severe and prolonged seizures, sometimes three in one day. Now his blank expressionless face held the look of a child who had suffered from years of serious epilepsy.

She said, “I heard that you can sometimes help people.” I said, “Yes, sometimes we can.” She didn´t ask for money, clothes or food. She wanted her children well. These two sick children, Loewuo with the seizures, Losieku with the spinabifida, were far too ill for us to treat at our small dispensary. But by chance, late the following morning, the aircraft would be flying empty to one of the only two hospitals in Tanzania with a neurosurgeon. I asked her to be here early and told her it would not cost her anything. The expenses of the one hour flight were already covered by the hospital which needed the plane´s services later in the day. She arrived here three hours after the plane had left.

Although I shouldn´t have been upset, I was frustrated with her for losing such a good chance. She let me tell her how disappointed I was. Then she simply said, “I´m sorry,” and started to walk away. I followed her. I wanted to know why she would waste such an opportunity. She answered quietly: “We live high up the mountain. I was awake before dawn trying to get the children ready. Then we started walking at the first light of day. But Loewuo had a seizure and we had to wait for him. Then he was so tired and weak that he could only walk short distances before resting. I had to help him to stand up and push him forward to start him walking again. Although I saw we would be late, I so badly wanted the children to be treated that I continued on, thinking perhaps the plane would still be here.” Even though she had missed that flight, two weeks later the plane was making another trip to the same hospital and the visiting neurosurgeon was still there. This time, leaving the 11 year old daughter at home to take care of the cow and goats, Ndepayan and her two sick children didn´t miss the flight.

That was four weeks ago and today they are back. Loewuo´s suspected epilepsy – was not epilepsy but a rare disease of the mitochondria in the cells. Even in Europe or America the prognosis is bad; but high-line anti-epileptics do reduce his seizures. Losieku´s spinabifida is skillfully closed up and he is growing so fast that in a short time his mother will not be able to carry him. We´ll have a physiotherapist and orthopedic specialist work with him; and with their help he will soon take his first step. We believe that with the aid of crutches he will be able to walk alone.

Ndepeyan brought me some fresh peaches from her tree.

Sophia

30 DECEMBER 2006

30 DECEMBER 2006

My name is Sophia. It means wisdom. I don’t feel wise. I don’t feel much of anything except pain. Pain in my face. Pain in my heart.

I can’t look into a mirror. What is there is horrible. What’s not there is even more horrible. This shouldn´t happen to any 17 year old. It shouldn’t happen to anyone.

When I was a little girl, I got sick. The sickness ate away the side of my mouth. Soon there was almost nothing left. Licking, trying to soothe the open wound, my tongue got stuck there. It healed that way. I couldn’t talk any more. I hid my face, wrapping it with a scarf. I looked out into the world with one eye uncovered. I couldn’t let anyone see in. Not strangers, not friends, not family, not even myself. My own mother rejects me.

What will become of me? How will I live? How will I have friends? How will I ever be able to get married looking like this? How will I ever have children? Who will walk with me through life? Who will take care of me in my old age? Only the past and present. No future.

Sometimes I dream. I dream simple dreams: that people can look me in the face without being frightened, without turning away. I dream that I can smile again, that my face is whole again, that my tongue is loose again, that I can move it, that I can just put it back inside my mouth and stop drooling all over my clothes.

You can, can’t you? Move your tongue? Say a word? Smile? Look out on a world that doesn’t turn away from your face? How simple. For you.

I live in a small village, far from even a small town. One day an airplane came to my village. The pilot’s name was Elisabeth. She saw me. She said: “Come with me. Maybe we can fix you up again.” I laughed. Even in my dreams this didn’t happen. But it wasn’t a dream. It was better.

I now have a mouth, a tongue that is free. I can smile. I can look at people, and they look back at me instead of looking away. Simple, you say. Oh yes, but how wonderful!

Sophia is recovering from extensive plastic surgery made possible by many people working together. She was found in a remote village by Flying Medical Service pilot Elisabeth Meeus while doing regular clinic flights to distant areas which have no other ordinary health care services. She was treated by medical experts who donated their services. She now attends Olkokola Handicapped Training Center. But in a short time, she’ll be handicapped no more. Olkokola has 28 other students like Sophia who learn a series of skills to help them be self-supporting. Last year Flying Medical Service pilots and staff flew more than a thousand hours and treated 21,055 patients. Sophia was one of them.

Thanksgiving Day

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

25 November 2004

In a most spectacular way I almost didn’t survive today. So, although this is a national day of Thanksgiving in America, I am thankful to be alive in Tanzania.

Rebecca Moran, our newest Flying Medical Service pilot, joined us last week. We had just returned from a medical flight and were refueling the plane. I was sitting on the wing holding the fuel hose pressurized with high octane aviation gasoline when suddenly Rebecca and the two BP fuel men, who were standing in front of the plane, turned with a shocked expression on their faces and disappeared under the wing. A twin engine aircraft with seven passengers on board had just taken off, retracted its landing gear, and begun to climb when an engine failed. It landed on its belly, slid down the grass on our side of the runway, and passed about six feet from where Rebecca and the BP men had been standing. The plane came to a stop less than ten feet from the fuel pump.

Parked just behind the fuel pump was a refueling tanker containing several thousand liters of jet fuel. This was not far from the Air BP fuel storage tanks which carry more than 50,000 liters of fuel. The plane stopped, nose to nose, only a few feet from a small plane which had just started its engine. Immediately behind that aircraft was a 49 passenger twin turboprop which had also just finished loading passengers and started its engines.

With only a slight change in the wind, or with the troubled aircraft’s engine stopping only one second

later, the newspapers might have read: Once upon a time there was an airport in Arusha. Flying Medical Service might have lost half of its staff and half of its fleet that day. As it was, there were no injuries whatsoever. The passengers from the crashed plane boarded another aircraft a short time later and arrived safely at their destination. And our all volunteer staff: Rebecca, Elisabeth, Jacek and I — we continue to love to fly. Last year we treated 6,989 patients, vaccinated 9,080 children, attended to 4,377 pregnant women, treated 421 TB cases, provided health education, medical specialists, medical training seminars and flew 195 seriously ill patients from their remote villages to various hospitals.

We also supplied radio communications, medicines, and logistical support to many health care facilities. We flew our two aircraft 818 hours. We did all of the above with much help from many others. We are grateful to you all.

Today’s incident reminds me how fragile and yet how resilient life is. It recalls a story of a Franciscan priest who was caring for victims of the 9/11 disaster in New York. He was himself killed when the buildings collapsed. He had a favorite saying written on a placard on his desk: If you want to make God laugh, tell God your plans for tomorrow. They engraved that saying on his tombstone.

Despite the many serious and very real problems in the world, there is also much much goodness, and many reasons to laugh.

On behalf of all the staff at Flying Medical Service and Olkokola Handicapped Training Center, I wish you a wonderful and happy Christmas.

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

Tanzania 2003

We jokingly call him Lepilal the Lion Killer. But it was no joke what happened to bring about the name.

Lepilal Lorminis is his real name. He is 19 years old. He was herding cows as he often did quite some distance from home. A lion slowly approached his herd of cows. Lions are abundant in the area, but they more often hunt wild animals. Still, Lepilal was cautious. The cows couldn’t defend themselves. Lepilal was their only defense. And he, dressed in traditional Maasai warrior fashion, had only a spear in hand and a short sword at his side.

The lion was determined. So was Lepilal. The lion approached the herd slowly and deliberately. Lepilal called for help, but the wind and distances between him and the other herders masked his voice. The lion threatened. Lepilal stood his ground and threatened back. This back and forth sparring went on for what seemed to him like an eternity, but was — he guessed — maybe 45 minutes. Finally the lion attacked. Lepilal’s spear went into the chest and out the side of the lion. But the lion grabbed Lepilal by the throat, crushing his windpipe and tearing it open. The lion died shortly after. Lepilal staggered towards the nearest group of fellow herders, unable to shout, barely succeeding in stopping the bleeding.

“Mike Sierra this is Loliondo” crackled the radio. Mike Sierra, the radio phonetic alphabet for the letters MS (medical service) is our call sign. Flying Medical Service was being called by Wasso Hospital in Loliondo in the northern part of the Serengeti plains, a full day’s drive from us, one hour by airplane. “We have a Maasai warrior badly injured,” the doctor explained. “We can’t handle the situation here. Can you take him to Nairobi?”

We could, of course. The expenses of the aircraft were small compared to what the hospital bill would be. Who would pay? The hospital said they couldn’t. Well… I didn’t know. In the end, we carried the bill from Flying Medical Service funds and from gifts given to us for poor patients.

Almost a full month later, when I was letting Lepilal out of the airplane after reaching home again in Loliondo, he asked me what it all cost. I told him he owed me 84 cows or 42 wives. His choice. He laughed, but then said quite seriously: “It may take time, but I’m determined to pay this back. I have five bulls that I am taking tomorrow to sell in Narok.” I believe him. I told him he was alive because of people he’d never met. He had a new chance at life. He should try to make it a good one.

Olkokola, Tanzania, Thanksgiving Day

Olkokola, Tanzania, Thanksgiving Day

22 Novermber 2001

Dear Friends,

The poet Emily Dickinson once wrote that “Hope is a thing with feathers.”

Woody Allen wrote many years later that “Emily Dickinson was wrong, hope is not the thing with feathers. The thing with feathers is my nephew. I must get him to a specialist at once.”

In reality, the thing with feathers is my neighbor, Musenge.

Musenge first appeared here years ago, a woman of about 35, dressed in black, lurking around corners, wearing beads and feathers in a way no one in this area would ever wear. Her eyes were wild and on fire. She would shout at people and make threats, shaking her fists or sticks and – yes – her feathers at them.

We have here a small trade school for 30 physically handicapped young adults. Musenge would also threaten the students, speaking in strange languages, running up to them and pretending to hit them. The students would shout and scream and run away, laughing at her.

She was harmless. But she was hurting inside. She had a family she could no longer care for. There was a loud sound which she described “like a grinding mill” constantly inside her head. And then there were the voices. The voices would come, and she had to follow them. If she didn’t, they would become unbearable.

In her dysfunction, she had a function in this society. People believed she was possessed by a

spirit who could prophesy. She often walked around with her young daughter who would “translate” the gibberish that she spoke. And people gave her a little money for giving them a message about the future. But she was hurting inside.

When she came, I didn’t run, I didn’t laugh. I had worked with people with mental illness before. I asked the students not to make fun of her. I asked them to treat her, as if she were their own mother who had problems. They quickly became more sympathetic and changed their behavior to her. And – at least in this one small place – she changed her behavior. She felt welcome. People didn’t run. She didn’t threaten. She would sit for hours, speaking her strange “languages,” and sometimes ask for a glass of water to drink. Occasionally she would ask to talk with me. I would talk with her when she would agree to use a real language. I explained to her that I would go inside to do other work when she felt she had to speak the other “languages.” She could call me when she wanted to speak Swahili or Maasai. (After all these years I still need lots of help understanding Maasai). She never asked for much time. Finally one day she agreed to try some medication.

She is still on it after several years. There have been ups and downs. But since starting the

medication, she lives a pretty functional life, attends a monthly mental health clinic run by Medical Missionary Sisters, and takes surprisingly good responsibility for other disturbed and handicapped people in the area. We tried hiring her for some day work, but she can’t work much. Still, with her own limitations, she does

amazingly well.

She is now building a small shed where she hopes to keep two milk goats. Her hope is that, even in the dry years when food is scarce (and we have many of these), her goats will survive better than cows or crops. I think she’s right. We’ll help her get a couple of milk goats.

With the heightened feeling of uncertainty in the world these days, I’ve been more aware of the need to listen very carefully to the voices from other people, to the ways they hurt, to the ways they hope, even if we can’t hear and understand all the same voices.

Two thousand years before this Christmas, the world was a violent place. Misunderstandings and conflicts abounded. Into that world a very fragile message, a feathered message, was born. Maybe both Emily Dickinson and Woody Allen are right. And maybe we can all dust off our feathers and learn to fly a little better.

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

November 2000

The skeleton stood in front of my door. The breeze blew a strong, sweet, rather pleasant fruity smell towards me.

The 17 year old skeleton was called Anna.

She said simply: “Help me. I’m dying.” And she was.

It’s too easy to look at emaciated people here and assume they have A.I.D.S. Many don’t. Anna didn’t. She had tuberculosis and diabetes. Her blood sugar was 16 times higher than normal! Without TB treatment and regular insulin injections, she would soon be dead.

Now, nine months later, she is a healthy young woman with possibilities ahead of her that she hardly could have dreamed of only a short time ago. Her tuberculosis is cured, but her monthly insulin maintenance costs more than a full month’s minimum wage here in Tanzania . We are trying to set up a fund for people like Anna, to help them just to keep alive and healthy.

In cases like these, the differences between more developed and less developed world are stark and shocking. Anna’s insulin, syringes, and minimal blood sugar testing cost $ 110 per month. In contrast, a day-laborer here earns only about $ 36 a month. Compare that with a minimum wage earner in the U.S. who would earn the same in less than a day, and you can begin to see the magnitude of the problem, especially when you realize that most basic commodities – like food – are more expensive in Tanzania than in the U.S.

There are many people here like Anna. This year we saw the gunshot-wounded, those injured by wild animals, the crippled, the twisted, the blind, those who hear strange voices in their heads, the diabetics, the alcoholics, the uncared for, the hungry, the burned, those affected by AIDS, the orphaned and the poor. We also saw the misdiagnosed who came for often life-saving second opinions, second treatments and second operations. They all have names. They all have stories to share with us.

In the midst of it all, ordinary people showed patience, trust and care in often extraordinarily demanding circumstances. This morning, for example, a young mentally disabled girl, hardly able to take care of herself, came to report that her mother was seriously ill with malaria and asked for medicine. She is one among many. Their stories fill unwritten volumes.

And more than ever before I realize how much we live in a world filled with heroes and heroines, most of whom are so humble that they pass unnoticed, unheralded, uncelebrated. Yet they have profoundly touched the lives of one, or some, or many of us.

Christmas 1999

Christmas 1999

“So who are you to me: acquaintance, friend or enemy?”

The hyena watched the 11-year-old girl and her aunt carrying buckets of water on their heads. He had watched them before, and many others like them. Why was he so angry today? What was wrong with his mouth, his stomach, his head? The world had never looked the same since he got bitten a few days back by that crazy fox. “My throat,” realized the hyena, “is so dry; but today I hate the sight or even the thought of water.”

Some water trickled out the top of Sinonit’s bucket onto the side of her face. She smiled… “So cool,” she thought, “in the hot sunlight.” Suddenly the weight of the hyena was on her, crushing her jaw, breaking every bone in her head. Her aunt dropped her own bucket and tried to pull the hyena away from Sinonit. What was going on? Hyenas don’t attack people in broad daylight! The thought was not finished before the hyena jumped on her, too, ripping into her shoulder.

The warrior ran, leg muscles almost tearing to make him race faster. At the same time he aimed at the twisted bodies, fur and human flesh struggling and intertwined. With practiced eyes and arm connected by panic to a brain set on edge by adrenaline, he let his spear fly with full force.

“What is wrong? So full of hurt. So hard to breathe. This new taste in my mouth. Red everywhere.” So thought both the hyena and Sinonit. The next two breaths were the hyena’s last, a spear through lung and heart. But Sinonit kept breathing. She tried to cry. What is wrong? Eyes don’t see; my mouth, my face, my head, they hurt so much.

Three doctors, Wolf, Nicolas, and Gerard, all with long surgical experience in Africa, both in peace and in war, were horrified at what the Maasai warrior brought to them: Sinonit’s still struggling tiny body so horribly disfigured by the bites of the rabid hyena. One doctor prayed that Sinonit would die quickly to be out of her pain. Her head was so disfigured, her throat so damaged, she couldn’t possibly survive. But she did. She tried to cry. She struggled with death, with life.

I was flying 140 miles south of Wasso hospital when Wolf, the doctor in charge, called urgently on the radio. “Please come as fast as you can. We have a little girl badly injured by a hyena. She’ll die if we don’t get her to a major hospital quickly.”

That was the 12th of November. I flew her, head totally wrapped up, breathing tube in place, pulse racing, across the border of Kenya and Tanzania, to Nairobi. She was on the operating table at 5 PM and the surgeons worked till 2 o’clock in the morning.

She’s now walking around, able to talk with some pain, sight in one eye, awaiting two more major operations to reconstruct her jaw and skull with titanium plates, and hopefully restore sight to the other eye. The doctors hope she will be released and ready to go home on Christmas Eve, seeing, walking, and talking. What a nice Christmas present to a family.

Of course, she is the million shilling girl. The expenses of such an operation are enormous, and you can imagine that a family of Maasai herders don’t have hospitalization insurance.

People have been pulling together, offering support, from the president of one of our East African countries, to complete strangers. It’s of course what should happen in a world where Christmas makes sense.

And other good news: after the loss of one of our aircraft last year and the resulting deaths of three people going to work at the same Wasso hospital where Sinonit was first seen, Flying Medical Service expects our replacement aircraft to arrive in January, again with the help of so many people.

With only one aircraft, Flying Medical Service did 68 emergency flights this year, and treated and vaccinated 15,112 people, an average of 41 patients a day.

Our technical center for the physically handicapped is training a new group of 30 more men and women.

The rains have come; the fields are green; there should be plenty of food this year.

I am happy, and well, and loving living here.

I hope it is the same with you, wherever you might find yourselves.

Merry Christmas and a Happy Millenium.

Dear Friends,

7 December 1998

It was the saddest Christmas of my life, the Christmas of 1996. The Christmas of 1997 was – without doubt – the most intense and tense. Till now, time to write has simply not been available. The following is an attempt to keep you up to date, while I’m wondering what next Christmas will bring.

Bagamoyo, Tanzania

Bagamoyo, Tanzania

November 30th. Departed Dar Es Salaam 20 minutes ago.

The rain pounded hard on the aircraft windshield. Zero visibility. Solid instrument weather conditions. Suddenly, with hardly a warning, total engine failure.

We were six adults and one infant on board, including the doctor in charge and the matron of one of the largest hospitals in Tanzania. No one panicked — for which I am grateful. We descended from 7,000 feet to about 1,200 feet before breaking out of thick clouds. We were still in heavy rain. Below us were palm tree plantations and rice paddies. The Ruvu River was high and the whole area was a swamp. Marian, who is our medical director, is also a surgeon and a pilot. She was flying. I was in the co-pilot’s seat. When the engine quit, this arrangement allowed for good trouble shooting and good flying at the same time. We landed in an unused rice field. There was no damage whatsoever to the aircraft or passengers or any property.

The problem turned out to be a faulty design in two ignition harness couplings that allowed the spark plug wires to short out in heavy rain.

We spent two weeks cutting an airstrip through the eight-foot-tall elephant grass and trying to get the soggy earth to dry out. It took another two weeks to cut thirteen drainage channels to the side of the airstrip. The day before Christmas Eve, we thought we were finished and would be able to leave early the following morning. .Surprise!

A week before, and one hundred miles away, El Nino rains caused massive flooding of the Ruvu River. We hadn’t heard about it. Though far downstream, we were only about a mile from the river. On the morning of December 24th the flood crest reached us. We walked to the airstrip to find not an airstrip but a lake. We spent the day and night before Christmas and all Christmas day and evening frantically building a 2×4 lattice work under each tire, slowly jacking the plane up inch by inch till we had the tires three feet above the swamp (always keeping just ahead of the rising water).

In the following days, we had to swim to work every morning, with a machete in one hand and a flare pistol in the other. The Ruvu river has plenty of crocodiles. There were also pythons the thickness of my upper arm. One day even a hippo showed up to visit the aircraft on our makeshift runway. The airplane was seven miles from Bagamoyo town. We lived in a mud and grass hut during those days. We shared the hut at times with a giant monitor lizard, which liked to live between the top of the wall and the grass roof, and a green snake which I always hoped was a coconut snake and not a boomslang. Boomslangs are one of the most poisonous snakes in the world. We never found out what it really was.

In the following days, we had to swim to work every morning, with a machete in one hand and a flare pistol in the other. The Ruvu river has plenty of crocodiles. There were also pythons the thickness of my upper arm. One day even a hippo showed up to visit the aircraft on our makeshift runway. The airplane was seven miles from Bagamoyo town. We lived in a mud and grass hut during those days. We shared the hut at times with a giant monitor lizard, which liked to live between the top of the wall and the grass roof, and a green snake which I always hoped was a coconut snake and not a boomslang. Boomslangs are one of the most poisonous snakes in the world. We never found out what it really was.

We flew the aircraft out of the swamp on January 16th, using barely half of the runway we had prepared. We beat the beginning of the rainy season by only minutes. The long rains here last three to four months. On the 20 minute flight to Dar Es Salaam that day I ran into torrents of rain. The long rains didn’t stop till May.

This story, despite its difficulties, had a happy ending. It doesn’t always work out that way.

On September 17th, our newest Flying Medical Service pilot, an experienced flight instructor from New Zealand, flew into the side of a mountain with this same aircraft. He, the doctor in charge of Wasso hospital, and a radio engineer were all killed. We’re trying to gather funds to replace the $ 140,000 airplane. But Dennis Tindill, Saeed Mottaghi, and Hussein Mahamoud aren’t replaceable.

Steve and I now struggle along with one airplane, trying our best to meet the medical needs in

distant areas.

As Christmas draws near, I recall that historians put Jesus’ life on this earth at perhaps 33 years.

This year I turned 50. What strange things, what wonderful things, those years have been. I don’t know what this Christmas will bring, except surely new surprises. And I think of you, with fond memories, with large hopes, and with much happiness.

Merry Christmas and a happy and hope-filled new year.

Olkokola, Tanzania

Christmas 1996

Christmas 1996

The Rwandan refugee camps in Tanzania are now officially closed. Five days before Christmas everyone was ordered out. 485,000 people were on the road walking in the rain. The young, the old, the healthy, the sick and dying. The line stretched on for 60 miles. There were an average of 30 babies born each day on the way, a strange sort of replay of the Christmas story many thousands of times over. No room. No time. No space. No more food. The door is shut. Go to your own country, to your father’s and mother’s house, and be counted. And then…?

There were four of us in the small bush plane. Our Flying Medical Service doctor sat next to me in the co-pilot’s seat. The two seats behind us were occupied by the nurse in charge of the medical work in the Chabalisa refugee camp, and next to her the logistical officer for the Memisa medical teams. The two rear seats and the cargo pod were filled with their sparse luggage, and reams of reports.

We flew over the long lines of soaking-wet refugees one last time, hardly able to contain our sadness. It was difficult feeling anything other than that we had somehow failed these people.

I now think of something that Audrey Hepburn once said:

“People, too, are part of the environment. They need to be protected, cared for, preserved, renewed, recycled, and redeemed and redeemed and redeemed, again and again and again. People should never be just thrown away. They must always be welcomed.”

Despite many people’s efforts, Rwanda and Burundi remain unstable to this day.